Improving Passage Retrieval with BERT

Improving Passage Retrieval with BERT

By Ashlan Ahmed and Yael Stochel

Problem Overview

Open-domain question-answering tasks involve identifying answers to questions from a large corpus of documents. To get accurate answers to a given question, it is first necessary to narrow down “candidate” passages from the large corpus, and then search for the answer in the selected passages. The former operation, called retrieval, is essential, allowing the correct answer to be returned without the inefficiency and risk of looking through superfluous, irrelevant passages.

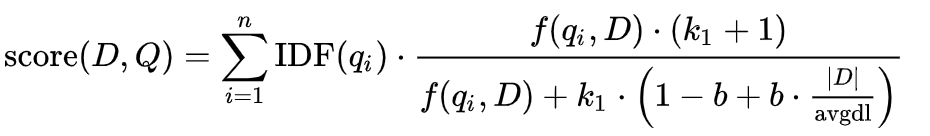

One of the most popular methods for retrieval is BM25, BM meaning “best matching”. It is a function that ranks a given set of documents based on how relevant they are to a query. On a simple level, it uses a formula to calculate a “score” for each document based on a number of factors, including query frequency in the document and average document length in the corpus. Since BM25 is term-based, high-dimensional vector representations for documents can be stored and quickly accessed, allowing for efficient retrieval even over a large number of documents.

Though BM25 offers considerable benefits in its efficiency, its use of term-based sparse representations curtails its performance. The authors of “Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering,” the paper upon which we based our project, explained one example of this shortcoming. Consider the question, “Who was the bad guy in Lord of the Rings?” A passage that included the sentence “The villain in Lord of the Rings, Sauron, violently rules the land of Mordor” would not be ranked highly by BM25 since the term-based representations do not account for synonyms. Aside from the nuisance of requiring precise wordings in questions, this fault may even prevent the retrieval from returning the passage with the correct answer.

Using the power of state-of-the-art natural language models such as BERT, we can create representations that capture the context of a word (in queries and documents). Thus, our vectors are not term-based sparse representations, but dense encodings. In contrast to BM25, which uses static representations for rankings, this involves using the RoBERTa tokenizer and training a model that learns to rank passages.

Implementation

We began by preprocessing our dataset, SQuAD, the Stanford Question Answering Dataset. Our strategy for training the model was to use both positive and negative reinforcement learning. For the positive passages, we preprocessed raw files for the questions and their corresponding “golden passages,” the passages associated with each question. The negative reinforcement required additional preprocessing to find appropriate negative examples, in order to train the model which passages not to select. We used both high ranking BM25 passages that do not overlap with the golden passage, and randomly selected passages as negative examples.

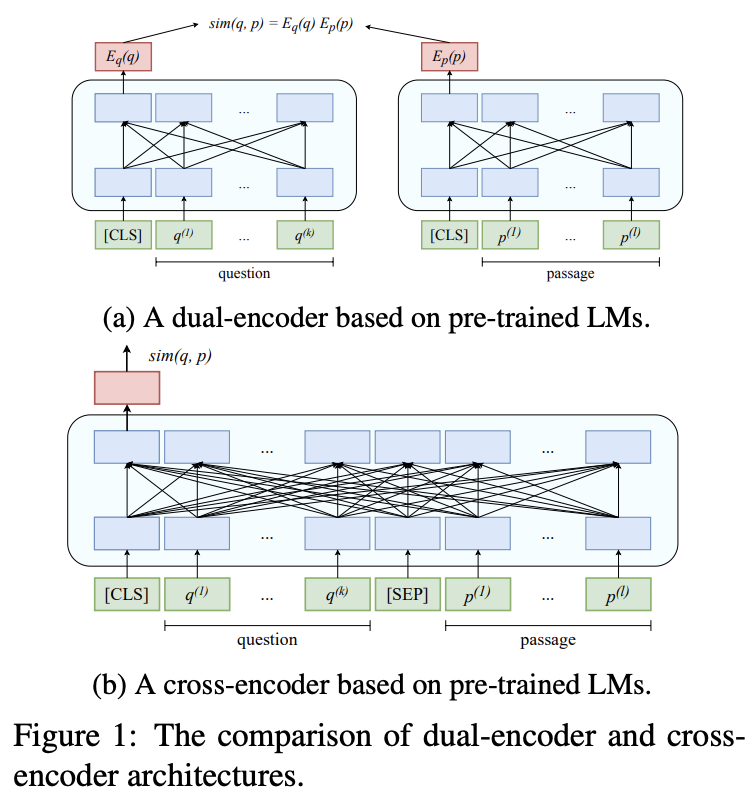

We then used the Roberta Tokenizer from the transformers library to encode pairs of each question with all of its potential passages, both positive and negative. These were stored in numpy arrays for later use by PyTorch’s Dataloader. During training, for each example the model was provided with, it outputted similarities, given by classification tokens, for every question/passage pair. The goal of the training was to maximize the value assigned to the question/golden passage pair and minimize the values assigned to the question/negative passage pairs. In this way, the model would learn which passages to select when provided with a query. The loss function compared the scores returned by the model to a matrix with the ideal similarity scores – a 1 for the golden passage and 0s for the negative passages.

Results

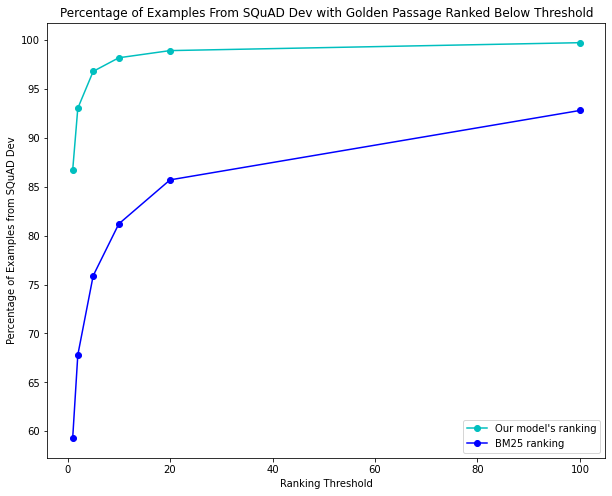

Our initial model, trained on one random passage and one BM25 passage with a linear learning rate scheduler, achieved an accuracy of 86.7% on the SQuAD dev set with an average rank of 1.43. Accuracy represents the percent of all dev questions (11864) where the model gave the golden passage rank 0 (“perfect” ranking). For each question, the model provided rankings for all 1204 dev passages. The results compared to BM25 can be seen below.

We also tried changing hyperparameters, such as changing the learning rate and trying out other learning rate schedulers (polynomial), and adding more negative passages. Results were nearly similar or worse to the original training described above: the polynomial scheduler achieved 77.3% accuracy and an average rank of 2.33 (4 negative random passages, 4 negative BM25 passages).

Future Directions

In addition to the cross-encoder architecture described above, we hoped to replicate the dual-encoder architecture described in the DPR paper on the SQuAD dataset. While we did not finish building the model or see results, the key difference from the cross-encoder was that queries and passages were tokenized individually (hence “dual”). As a result, we have two identical heads (one for question encoding, one for passage encoding), and construct a “similarity matrix” for the questions and different passages; the entries are calculated by taking the product of the question representation and the passage representation (see DPR paper for details). A “bonus” from encoding separately is that we can use in-batch negatives for negative passages (the other golden passages in a batch are negatives for other questions). This would allow for fewer model calls since we can reuse previous ones in a batch, speeding up training. Along with in-batch negatives (which are essentially random passages), we include the highest ranking BM25 passage that was not the golden passage. Ideally, the model learns to give scores close to 1 for the golden passage and scores close to 0 for irrelevant passages. We anticipate that this dual-encoder model would be faster yet have lower accuracies than the cross-encoder, due to not receiving added information from question-passage pairs encoded together, but do not have data for this.

Conducting more experiments by changing hyperparameters could also provide interesting results. For example, the DPR dual-encoder paper found that training with one BM25 negative had better results than training with multiple BM25 negatives. Since the cross-encoder architecture combines these “hard” passages with the question, it may be able to learn more from multiple BM25 negatives than under the dual-encoder architecture.

Further testing with a larger corpus size, and potentially training this existing model for longer on a larger corpus, would yield interesting results about how scalable this retrieval method is. As of now, it is mostly suited for smaller corpora, such as re-ranking tasks.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nima Sheikholeslami for his mentorship and introducing us to this problem. Thanks to the whole NLMatics team for making this an amazing summer.

Sources: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2004.04906.pdf https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okapi_BM25 https://huggingface.co/transformers/model_doc/roberta.html https://arxiv.org/pdf/2010.08191.pdf