Teaching BERT to Solve Word Problems

Teaching Bert to Solve Word Problems

By Yael Stochel and Ashlan Ahmed

Introduction

In the world of natural language models that are capable of answering questions given a corpus of text, there remains a category of questions that are easily solved by humans, but pose an additional challenge to machines. As the most basic example, imagine a dataset of simple elementary-level math word problems. For most humans, it is simple to identify the two operands and the operation required to provide the correct final answer. Yet, machines trained to provide spans of text when asked a question are incapable of performing this simple task. Though math problems are a simplified example of such a category, when considering any text with a quantitative focus, such as financial or census reports, the ability to answer such questions would provide considerable benefit. This summer, under the guidance of Nima, we aimed to train a model capable of answering questions that require performing an operation over two operands.

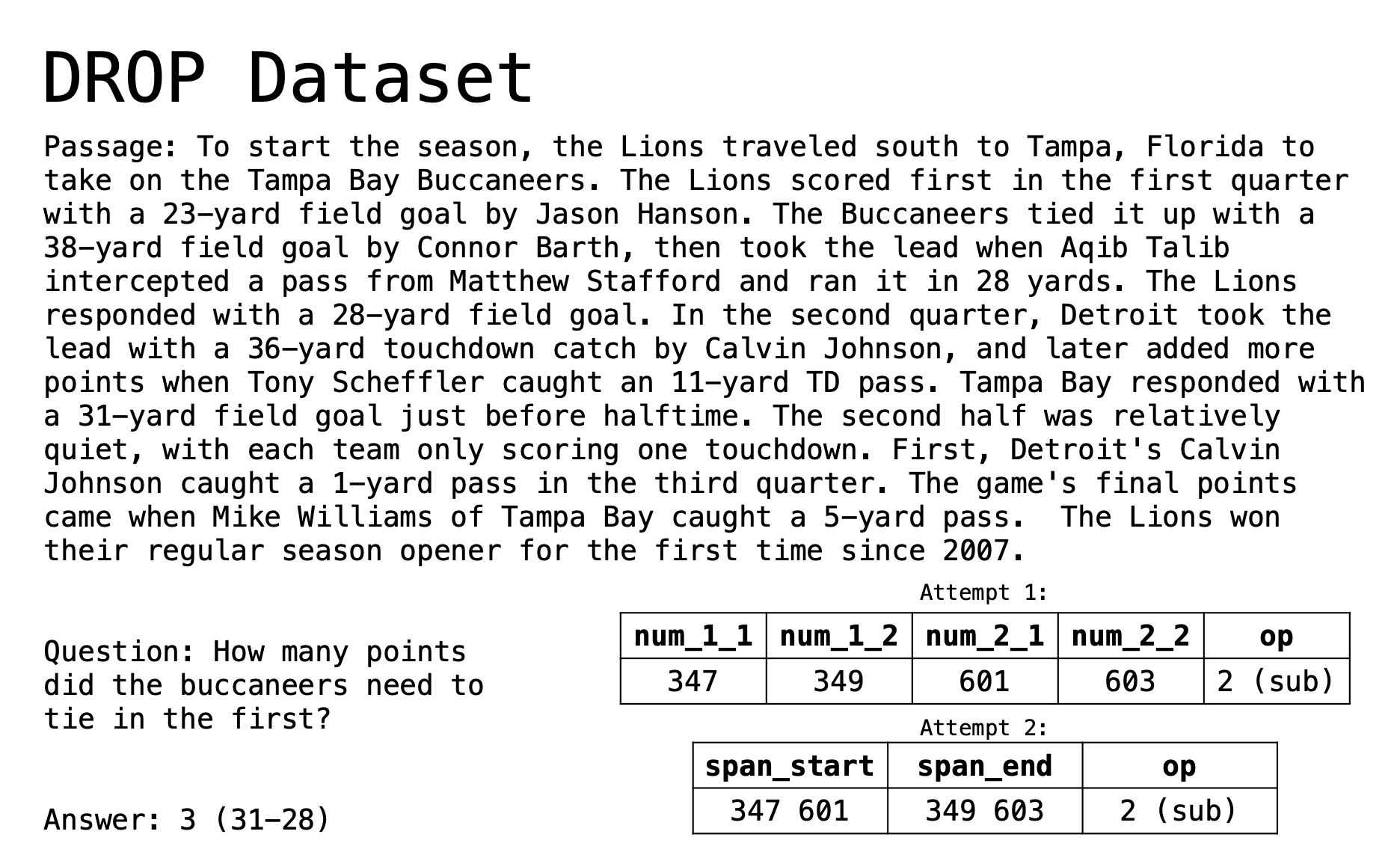

The basis for this task was the paper “Giving BERT a Calculator”. As the authors of this paper do, we used the DROP dataset, A Reading Comprehension Benchmark Requiring Discrete Reasoning Over Paragraphs, from AllenNLP. This dataset includes divisions into a training set of examples, to feed to the model during the training process, and a dev set of examples, for evaluating if the model is learning successfully. We trained our model using fairseq, and considered several different approaches to our training. It was also crucial that our final model have a high accuracy on the original SQuAD dataset, to ensure that it is still capable of answering the same questions as the original model in the pipeline.

Method

The DROP dataset includes several types of question/answer pairs. Some questions can be answered by a span of text from the original passage, while others have numerical answers. Within the category of numerical answers, some questions are considered counting questions, in which the answer must consider the number of times a certain event occurs in the passage, while others require performing an operation on two operands from within the passage. Given the nature of our project, we focused on the latter category of questions. Unfortunately, the DROP dataset only provided the final numerical answer to these questions, and not the intermediate step of the two operands required from the text. We briefly considered attempting to train a model capable of performing such a task, but it added an additional layer of difficulty. Instead, we opted to use a brute force method to extract the intermediate numbers and operations required. We iterated over all the numbers in the passages to find the pair of numbers that summed or subtracted to the correct result.

We tried two different methods of preprocessing this information. We first created five additional labels to feed to the model during training: two files for the starting and ending indices of the first operand and two more files for the indices of the second number, with an additional file for the operation (0 denoting addition and 1 subtraction). The architecture for this model included two heads. One of the heads identified the spans of the numbers, returning four logits for every token in the passage. The first logit represents the likelihood that each token is the starting index of the first number; the second logit the likelihood that the token is the ending index of the first number; the third the starting index of the second number; and the last the ending index of the second number.

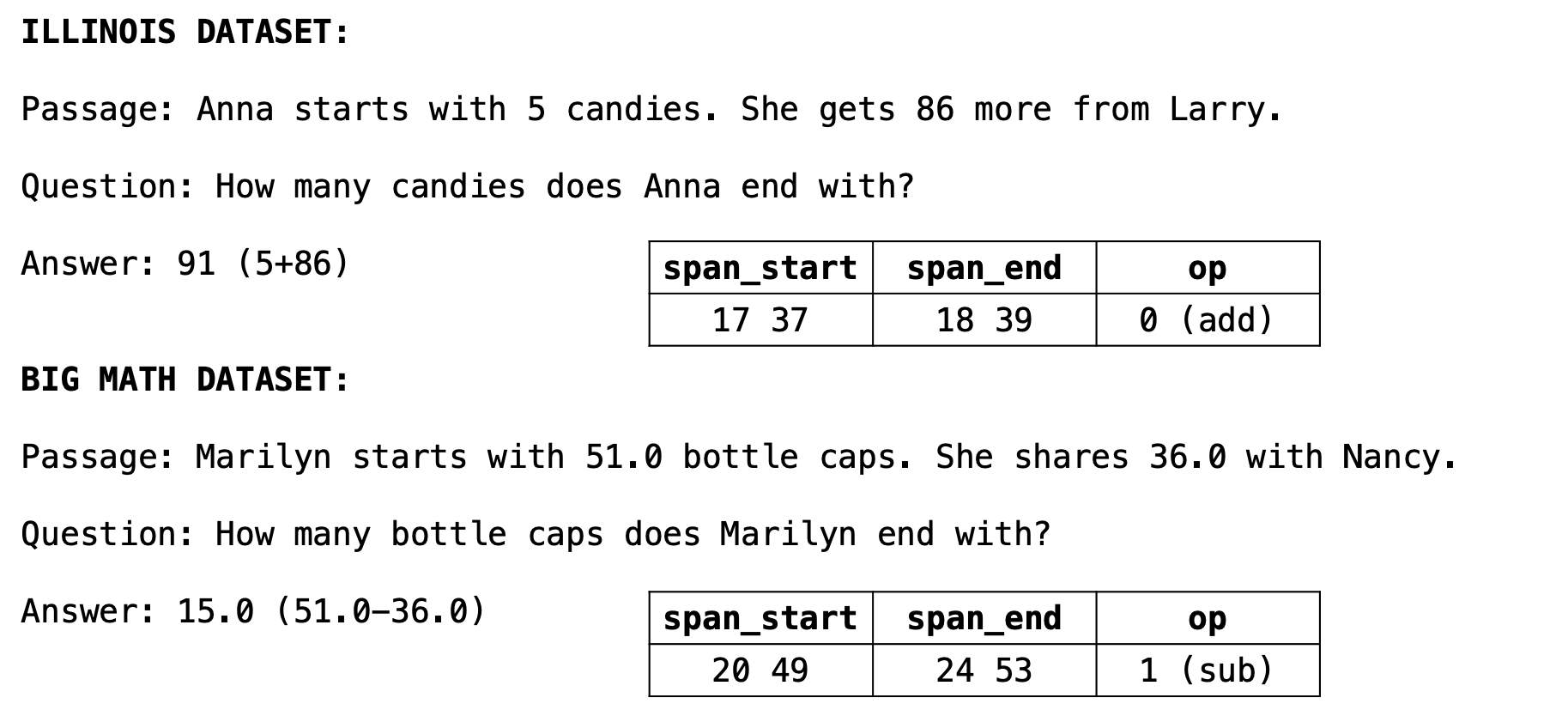

We soon realized that if we eventually want to expand the model to be capable of answering the DROP questions that require span answers, the preprocessed files require more flexibility. As a result, we instead created only two files for the labels – one file for starting indices and one for ending indices, with a space separating between different spans in the text. Using this method also provided the flexibility to consider multi-span questions, as for each additional span, we simply added another set of starting/ending indices to the appropriate files separated by a space. For this model, we used an IO version of training our model, which returned two logits for every token, the first representing the likelihood that the token is not within the span and the second the likelihood that the token is within the span. In order to enable the model to answer span questions, we added another operation possibility that denotes the question is answered by a span, and requires no operation.

Results

After trying both these methods, the accuracy achieved for the operation head was extremely high, in the high 80s, but the accuracy for the span head remained low, only reaching into the 50s even after adjusting the learning rate. The low success rate indicated that using the brute force method on the DROP dataset made the dataset too noisy; we could not be sure that the combinations of operands and operations given by the brute force method were correct and, in some cases, it was possible that some combination of numbers in the passage yielded the correct answer, even for questions that did not require operations.

As the size of the DROP dataset was such that cleaning it seemed unfeasible, we instead opted to find other simpler datasets. We came across the Illinois math dataset, a smaller dataset consisting of several simple math word problems which we augmented with other datasets online with similar simple word problems. Altogether the training dataset included over 1200 examples and the dev set around 350. Many of these datasets also include division and multiplication problems, which is beneficial for expanding the capabilities of the model. After completing the same preprocessing that we did for DROP, we ran the same model on the math problems dataset. On this training, the model yielded excellent results, with an accuracy rate in the high 80s for the spans and even higher for the operations. This model also maintained a high accuracy rate on the SQuAD dataset, successfully supplementing the existing model with the ability to answer simple math questions.

After the success of this dataset, we attempted different combinations of data to determine the optimal strategy for training a model. Among the methods we tried, we combined the DROP dataset with the math datasets, including the math datasets several times to account for the size discrepancy between the datasets. We also used the model trained on DROP to train the math dataset, hoping that the resulting model would retain what it learned from both DROP and math. We trained all of the models on a base model already trained on SQuAD, to ensure that we maintained a high accuracy on SQuAD. We found that any combination with the DROP data did not perform as well as the others, concluding that the best model, with an 86% accuracy rate on the math problems and an 88% accuracy rate on SQuAD, was the result of training the model on the combined SQuAD and math datasets.

Future Work

Though we successfully trained the model to answer simple math problems, there remains more work to be done until it is capable of solving more sophisticated queries. A first step toward accomplishing this task would be to find a suitable dataset, one in which the intermediate operands and operations are provided, preventing the noisiness of resorting to our brute force algorithm. Considering the moderate success we achieved even while using the messy DROP, it seems likely that with a cleaner dataset, this task could undoubtedly be accomplished using a training method similar to ours.

We would like to thank Nima Sheikholeslami for his mentorship and introducing us to this problem. Thanks to the whole NLMatics team for making this an amazing summer.